Blame traditional finance for the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank’s downfall was a product of traditional finance — critics shouldn’t conflate the issue with cryptocurrency.

The entire banking concept is based on the assumption that depositors will not want to withdraw their money at the same time. But what happens when this assumption fails? The answer lies in the asset-liability mismatch of banks, which can lead to disastrous consequences for the broader financial system.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), one of the leading banks for startups and venture capital firms in the United States, failed because of a liquidity crisis that has reverberated throughout the startup ecosystem. Silicon Valley Bank’s struggles shed light on the many risks inherent in banking, including mismanaging the economic value of equity (EVE), failing to hedge interest rate risk, and a sudden outflow of deposits (funding risk). Risk arises when a bank’s assets and liabilities are not properly aligned (in terms of maturity or interest rate sensitivity), leading to a mismatch that can cause significant losses if interest rates change.

The failure to hedge interest rate risk leaves banks vulnerable to changes in the market that can erode profitability. Funding risk occurs when a bank is unable to meet its obligations due to an unexpected outflow of funds, such as a run on deposits. In SVB’s case, these risks combined to create a perfect storm that threatened the bank’s survival.

Related: Silicon Valley Bank was the tip of a banking iceberg

SVB recently made strategic decisions to restructure its balance sheet, aiming to take advantage of potential higher short-term interest rates and protect net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM), all with the goal of maximizing profitability.

NII is a crucial financial metric used to evaluate a bank’s potential profitability, representing the difference between interest earned on assets (loans) and interest paid on liabilities (deposits) over a specific period, assuming the balance sheet remains unchanged. On the other hand, EVE is a vital tool that provides a comprehensive perspective of the bank’s underlying value and how it responds to various market conditions — e.g., changes in interest rates.

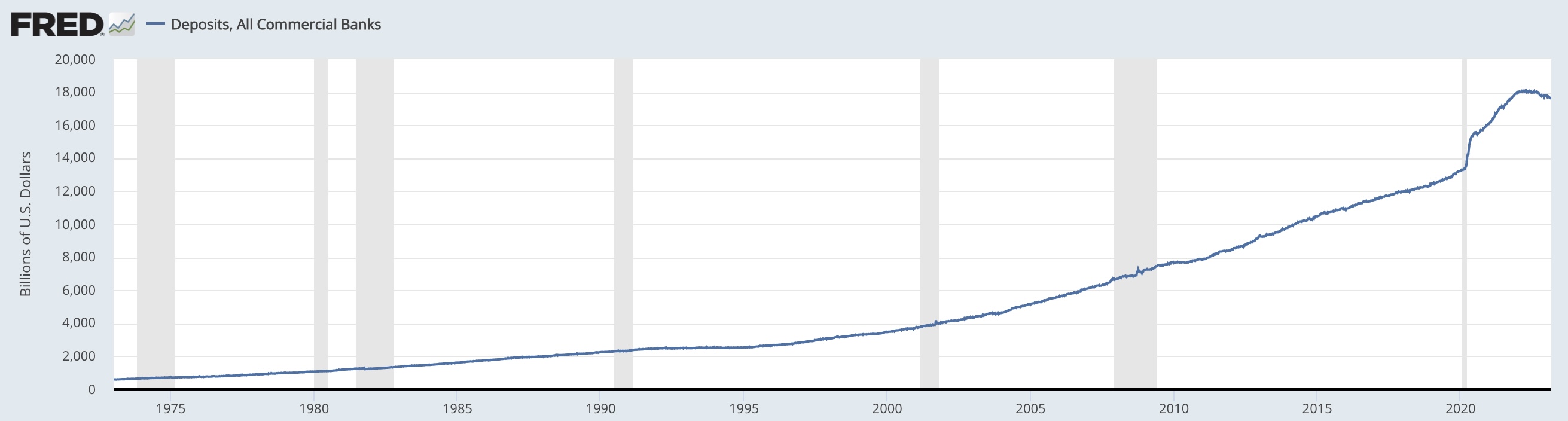

The surfeit of capital and funding in recent years resulted in a situation where startups had excess funds to deposit but little inclination to borrow. By the end of March 2022, SVB boasted $198 billion in deposits, compared to $74 billion in June 2020. As banks generate revenue by earning a higher interest rate from borrowers than they pay depositors, SVB opted to allocate the majority of the funds into bonds, primarily federal agency mortgage-backed securities (a common choice) to offset the imbalance caused by significant corporate deposits, which entail minimal credit risk but can be exposed to substantial interest-rate risk.

However, in 2022, as interest rates escalated steeply and the bond market declined significantly, Silicon Valley Bank’s bond portfolio suffered a massive blow. By the end of the year, the bank had a securities portfolio worth $117 billion, constituting a substantial portion of its $211 billion in total assets. Consequently, SVB was compelled to liquidate a portion of its portfolio, which was readily available for sale, in order to obtain cash, incurring a loss of $1.8 billion. Regrettably, the loss had a direct impact on the bank’s capital ratio, necessitating the need for SVB to secure additional capital to maintain solvency.

Furthermore, SVB found itself in a “too big to fail” scenario, where its financial distress threatened to destabilize the entire financial system, similar to the situation faced by banks during the 2007–2008 global financial crisis (GFC). However, Silicon Valley Bank failed to raise additional capital or secure a government bailout similar to that of Lehman Brothers, which declared bankruptcy in 2008.

Related: Why isn’t the Federal Reserve requiring banks to hold depositors’ cash?

Despite dismissing the idea of a bailout, the government extended “the search for a buyer” support to the Silicon Valley Bank to ensure depositors have access to their funds. Furthermore, the collapse of SVB resulted in such an imminent contagion that regulators decided to dissolve Signature Bank, which had a customer base of risky cryptocurrency firms. This illustrates a typical practice in conventional finance, wherein regulators intervene to prevent a spillover effect.

It is worth noting that many banks experienced an asset-liability mismatch during the GFC because they funded long-term assets with short-term liabilities, leading to a funding shortfall when depositors withdrew their funds en masse. For instance, an old-fashioned bank run occurred at Northern Rock in the United Kingdom in September 2007 as customers lined up outside branches to withdraw their money. Northern Rock was also significantly dependent on non-retail funding like SVB.

Continuing the Silicon Valley Bank case, it is evident that Silicon Valley Bank’s exclusive focus on NII and NIM led to neglecting the broader issue of EVE risk, which exposed it to interest rate changes and underlying EVE risk.

Moreover, SVB’s liquidity issues stemmed largely from its failure to hedge interest rate risk (despite its large portfolio of fixed-rate assets), which caused a decline in EVE and earnings as interest rates rose. Furthermore, the bank faced funding risk resulting from a reliance on volatile non-retail deposits, which is an internal management decision similar to the ones previously discussed.

Therefore, if the Federal Reserve’s oversight measures were not relaxed, SVB and Signature Bank would have been better equipped to handle financial shocks with stricter liquidity and capital requirements and regular stress tests. However, due to the absence of these requirements, SVB collapsed, leading to a traditional bank run and the subsequent collapse of Signature Bank.

Moreover, it would be inaccurate to entirely blame the cryptocurrency industry for the failure of a bank that coincidentally included some crypto companies in its portfolio. It’s also unjust to criticize the crypto industry when the underlying problem is that traditional banks (and their regulators) have done a poor job of evaluating and managing the risks involved in serving their clientele.

Banks must begin taking necessary precautions and following sound risk management procedures. They cannot merely rely on the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s deposit insurance as a safety net. While cryptocurrencies may present particular risks, it is crucial to understand that they have not been the direct cause of any bank’s failure to date.

This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal or investment advice. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Go to Source

Author: Guneet Kaur