The metaverse: Mark Zuckerberg’s Brave New World

Mark Zuckerberg attempts to create his own metaverse that would result in ever more centralization, leading to a dystopian future.

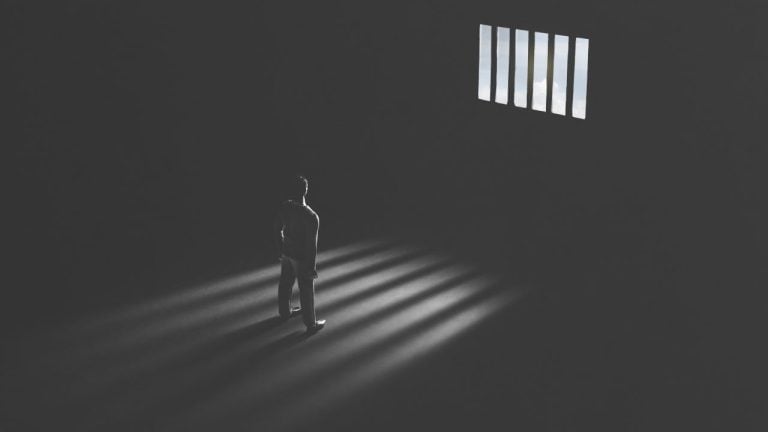

If Facebook happened to be a human being, where would he/she/they currently be? Most likely in prison… for a very long time. The company’s transgressions are too numerous to list. But Facebook is not human; it’s a company, and a very profitable one, at that. In fact, it’s now one of the most profitable companies in the world. Facebook’s market capitalization has recently surpassed the $1 trillion mark.

When we think of Facebook — more specifically, Facebook Inc. — we tend to think of a social media platform that is somewhat dated. However, it is important to remember that this multiheaded hydra is a conglomerate that owns 78 different companies, including WhatsApp and Instagram. In other words, Facebook is much more than cat videos and conspiracy theories. Spearheaded by Mark Zuckerberg, a champion of smoked meats, Facebook Inc. is a well-oiled machine. Its power is undeniable, and this power is growing. As Fortune magazine recently noted:

“Facebook, it appears, can’t be hurt — not by major ad buyers boycotting its service, not by state and federal investigations, and not even by a pandemic.”

The COVID-19 pandemic may have brought the world to its knees, but Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, hasn’t felt the effects. Last year, he had a measly net worth of $82 billion; today, it’s above $130 billion. Now, with Zuckerberg attempting to create his own metaverse, expect his value — and his power — to increase substantially.

The metaverse

Before discussing the metaverse, it’s important to ask one important question: What the hell is the metaverse, anyway? A blending of the words “meta,” which means beyond, and “universe,” the metaverse combines elements of the physical world and merges them with virtual spaces. American writer and author Neal Stephenson coined the term in 1992. Two decades later, no longer confined to the realms of sci-fi, the metaverse is almost upon us.

Related: Sci-fi or blockchain reality? The ’Ready Player One’ OASIS can be built

In this brave new world, the lines between physical reality and digital domains will become increasingly blurry. Nonfungible tokens (NFTs) and cryptocurrencies are already part of the metaversal experience, but going forward, in the actual metaverse, they will be combined with you, the user. Although we currently live, communicate and shop on the internet, once the metaverse comes into existence, we very well live our lives in the internet. Elon Musk wants to transport us to Mars, but Zuckerberg wants to transport us to, and place us in, the internet. Literally.

Related: The convergence between Tesla, SpaceX, renewable energy and Bitcoin mining

In a recent interview to The Verge, Zuckerberg described the metaverse as an “embodied internet, where instead of just viewing content — you are in it.” We will be tenants in Zuckerberg’s ever-expanding house. Rent will be paid in the form of data. This is not a comforting thought. As Wired’s Toby Tremayne noted, Big Tech firms like Facebook have “become walled gardens increasingly centralised and controlled by corporate interests.” Facebook already “owns WhatsApp, Instagram and Oculus,” which gives “them ownership of our friends, our behaviour, our gait, eye movement and emotional state.” Soon, if Zuckerberg has his way, Facebook Inc. will have even greater control over our lives. That, I argue, should comfort no one but Zuckerberg.

To access the metaverse, biometric data will be required. Eye scans, voice recordings, pulse rates, etc. All of this information will be collected by Facebook Inc. What will be done with this data? Considering Facebook has a sordid history of violating users’ data, this is an important question to ask. What laws, if any, will apply in the metaverse? If my avatar steals an asset, such as digital artwork, from another user, will I be punished? What happens if I live in Canada but my victim lives in Cambodia? If you think the world of crypto has its issues with crime, and it does, imagine the problems that the metaverse will present us with. Think Grand Theft Auto mixed with real-life scenes from Haiti or South Africa. Can we trust Facebook to police the metaverse? Of course not. Then again, who can we trust to police the unknown? World governments? Please.

Related: The data economy is a dystopian nightmare

For this piece, I reached out to Matthew Ball, a metaversal mystic of sorts. A venture capitalist, futurist and Silicon Valley-veteran rolled into one, Ball told me:

“The very premise of the metaverse means that more of our lives will be online, rather than just data relating to our lives.”

As for our economies, they “will run virtually rather than just be augmented digitally (i.e. via email, ecommerce, etc.).” Relocating to the metaverse, Ball warned, will intensify “many present-day risks, such as those of misinformation, data security, data rights (i.e. portability, right to be forgotten, disclosures), as well as the risks of platform control (e.g. Apple’s ownership of app standards, app distribution, app billing).” What we are witnessing is a digital evolution of sorts. The internet has changed the way we bring information, provide services and experiences online, but the metaverse — through goggles, headsets and haptic sensors — will revolutionize what it means to be human. Essentially, the metaverse will take us somewhere completely unknown. The question we must ask now, though, is: Should Facebook be the company to take us there, wherever there may be?

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Go to Source

Author: John Mac Ghlionn